|

Is Betelgeuse about to pop?

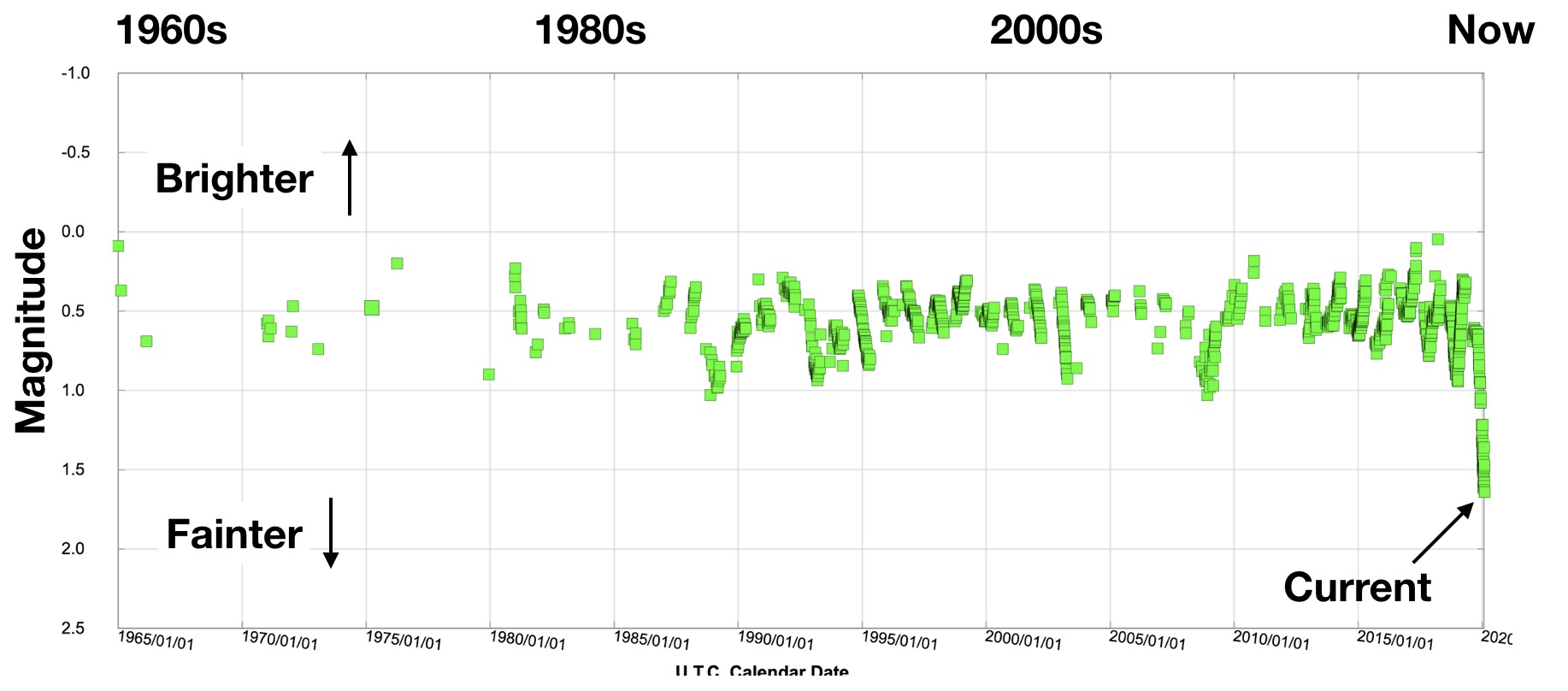

Betelgeuse (alpha Orionis) is one of the most recognisable stars in the night sky. Located in the contellation of Orion, it is (usually) bright, with magnitude of V~0.6.

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant. It left the main sequence about 1 million years ago, and has been a red supergiant for about 40,000 years. The radius of Betelgeuse is at least the size of the orbit of Mars, and at maximum diameter may possibly equal the orbit of Jupiter. It is a core-collapse SN II progenitor, which means that eventually, Betelgeuse will burn enough of its hydrogen that its core will collapse and it will explode as a supernova. This will occur sometime in the next 100,000 years. When it explodes, as seen from Earth, it is expected to briefly outshine the full Moon.

Betelgeuse is a semi-regular pulsating star: the brightness (or magnitude) varies. Betelgeuse's variability was first noticed in 1836, and in December 1852 it was thought by Herschel to be "the brightest star in the northern hemisphere", rivaling Rigel.

However, recently Betelgeuse has significantly dimmed. Although in 1927 and 1941 the magnitude of Betelgeuse dropped below V=1.2, current observations suggest it is fainter now than any time in the past ~150 years. We don't know why.

The current drop in flux could be due to two effects: the oscillations in the upper atmosphere may have entered a new state, causing the star to expand and cool; (ii) a significant dust production event could have occured, causing increased attenuation. More speculatively, Betelgeuse could be about to go supernovae.

The goal of this project is to measure the magnitude of Betelgeuse (over the course of a few weeks, time permitting), plot the light curve, and interpret the data.

Measuring the magnitude of such a bright star is not trivial, and so some novel techniques are required to carry out such an experiment. You can carry out one (or time permitting), both of these experiments:

1. Fast Imaging using the "lucky" camera

One way to measure the magnitude of a bright star is to take (very short) images, thus ensuring that the star does not saturate the detector. For this, we can use the fast "lucky" camera.

Familiarise yourself with the camera and its operation. You will need to be able to adjust the exposure time and field of view.

In the lab, take a few images at different rates, and become familiar with how and where the data is stored (be careful: it is possible to generate 1Tb of data in a few seconds!).

The images are likely to be read noise limited, so devise a method to measure the readnoise.

-

The linearity of the camera may be important for such an experiment, so exposures in the lab of a flat field, or on sky of a star field, may be required to check linearity and improve the data calibration.

-

If the images are short, the data may suffer from scintilation . and so have a measure of this effect may also be necessary. to properly calibrate the data.

- Design the experiment to take observations of the star. You will need to acquire the star using the CCD, and then flip to the lucky camera. Take exposures, noting that these will need to be very short images (ensure the image does not saturate!). In a short image on sky, there will be no comparison stars, and so a long exposure of a nearby star field will be required to calculate the zero-point of the image.

On the telescope, take a series of images of the star. You will probably want to take several 100 (1000s?) of images at millisecond rates. Once the images of Betelgeuse have been acquired, offset the telescope to a nearby star field, and take images (these will probably need to be several seconds).

Analyse each set of observations. We will need to calculate the conversion between counts/second and magnitude using the comparison stars in the "comparison star field" with counts per second on Betelgeuse. You may need to check the linearity of the camera and apply a calibration if necessary. Measure the scintillation, and adjust the calibration if necessary.

-

Finally, calculate the magnitude of Betelgeuse, and add it to the current light curve (see the links below). Is the magnitude continuing to fade? Given the uncertainties in the data, are more measurements during the next few weeks useful?

-

Is it possible to test whether the star is dimming due to dust? Taking data in each of the B, V and R-band filters might be interesting. Why?

Defoccussed Imaging using a CCD

Astronomers usually spend most of their time trying to improve the quality of their images, whether this is in terms of aligning their telescope and camera, building it on a high mountain site to get better seeing, or spending millions of pounds build adaptive optics modules.

A sharp image usually comes with the benefit that more of the photons are concentrated in to a small area, hence maximising signal-to-noise. However, with a bright star, this isn't helpful as a CCD camera observing Betelgeuse on a 14-inch telescope will saturate in much less than 0.03 seconds (which is the shortest exposure we can take)

One work around it is to significantly defocus the telescope, and hence "blur" the image. This will cause the light to be spread across a large fraction of the detector, hence making it possible to linearly sum the flux.

Familiarise yourself with the telescope, CCD camera and its operation. You will need to be able to adjust the filter and exposure time.

The images are likely to be read noise limited, so devise a method to measure the readnoise, and compare this to the dark current, and (ultimately) the photon and sky noise.

-

The linearity of the camera may be important for such an experiment, so exposures in the lab of a flat field, or on sky of a star field, may be required to check linearity and improve the data calibration.

- Design the experiment to defocus and take observations of the star. There will be no comparison stars, and so a long exposure of a nearby star field will be required to calculate the zero-point of the image.

On the telescope, acquire the target and take a series of defocussed imaged, making sure the image does not saturate! You will probably want to take several images. To calibrate, offset the telescope to a nearby star field, refocus and take images (these will probably need to be several seconds long to ensure enough S/N).

Analyse each set of observations. We will need to calculate the conversion between counts/second and magnitude using the comparison stars in the "comparison star field" with counts per second on Betelgeuse. Check the linarity of the camera and apply a calibration if necessary.

-

Finally, calculate the magnitude of Betelgeuse, and add it to the current light curve. Is the magnitude continuing to fade? Given the uncertainties in the data, are more measurements during the next few weeks useful?

-

Is it possible to test whether the star is dimming due to dust? Taking data in each of the B, V and R-band filters might be interesting. Why?

Some useful links:

AAVSO science alert (including a V-band light curve)

| Back to the AstroLab Home Page | ams | 2019-Feb-09 13:28:13 UTC |